Intrinsic Value Calculation: Buffett’s Way

Beyond Earnings: Harnessing the Power of Owner Earnings

Welcome to our guide on intrinsic value calculation: Buffett’s Way

In this post, we explore Warren Buffett’s timeless methods for determining the true worth of a company—from analyzing owner earnings and forecasting future cash flows, to discounting these flows to their present value and evaluating balance sheet strength.

Introduction

Owner Earnings: The Foundation of Valuation

Projecting Future Cash Flows

Discounting Future Cash Flows to Present Value

Adjusting for Balance Sheet Strength: Current Assets and Debt

Concrete Example: See’s Candies

Conclusion

1. Introduction

Intrinsic value is the bedrock of long-term, value-driven investing—it represents the true worth of a company based on its fundamentals rather than its current market price. This concept isn’t about chasing short-term fluctuations; instead, it’s a measure of a business’s ability to generate sustainable cash flows over the long run. By understanding intrinsic value, investors can identify opportunities where the market undervalues high-quality companies, thus setting the stage for significant long-term gains.

Warren Buffett, one of the most revered figures in investing, has long championed the idea that a company’s real value lies in its future earnings power. His approach is a harmonious blend of rigorous quantitative analysis and insightful qualitative judgment. As evidenced in his Annual Letters to Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders (Buffett, 1986; Buffett, 2007), Buffett emphasizes that one must look beyond superficial financial statements to the deeper, underlying economic realities of a business. He advocates for understanding the business’s true cash-generating potential—a concept he refines through measures like owner earnings—and for considering the quality of management and the competitive advantages that protect a company’s market position.

In this post, we’ll explore the step-by-step process of calculating intrinsic value the Buffett way. We begin with the calculation of owner earnings, which adjusts net income for non-cash charges and capital expenditures, giving us a more accurate picture of cash flow. Next, we’ll delve into projecting these cash flows into the future, a critical exercise in estimating sustainable growth. We then explain how to discount these future cash flows back to their present value using the discounted cash flow (DCF) method. Finally, we discuss the importance of qualitative adjustments, including applying a margin of safety to buffer against uncertainties.

This comprehensive approach not only reveals a company’s true worth but also embodies Buffett’s time-tested philosophy of sound, long-term investing.

2. Owner Earnings: The Foundation of Valuation

Owner earnings serve as a critical metric in value investing, providing a transparent view of a company’s ability to generate cash. Unlike net income, which can be influenced by various non-cash items and accounting nuances, owner earnings adjust for these distortions to reveal the true cash flow available to shareholders. The standard calculation for owner earnings involves taking net income, adding back non-cash charges such as depreciation and amortization, and then subtracting the capital expenditures required to maintain the business's current operations.

A refined formula for owner earnings is:

Owner Earnings = Net Income + Depreciation & Amortization−Maintenance CAPEX

It’s important to note that the capital expenditures subtracted in this formula refer specifically to maintenance CAPEX—the funds necessary to keep the existing assets operating efficiently. This is distinct from growth CAPEX, which represents investments made to expand the business’s capacity or enter new markets. Buffett’s approach, as detailed in his 1986 Annual Letter, focuses on the cash-generating ability of the business in its current state, which is why maintenance CAPEX is used in the calculation.

Buffett has long championed the importance of owner earnings because net income can be misleading if it fails to account for the reinvestments needed to sustain a company’s competitive advantage. By isolating the cash available after essential reinvestments, owner earnings provide a clearer picture of a company’s financial health and its potential to generate shareholder value over the long term.

Establishing owner earnings as the starting point is crucial for forecasting future performance. With a reliable measure of current cash generation, investors can more confidently project future cash flows—a key step in applying the discounted cash flow (DCF) method to determine a company’s intrinsic value. This focus on sustainable cash flow over transient accounting profits embodies Buffett’s enduring investment philosophy.

3. Projecting Future Cash Flows

Once you have a clear picture of a company’s current owner earnings, the next critical step is to project these earnings into the future. This process involves forecasting future cash flows—a fundamental part of determining a company’s intrinsic value. At its core, this forecasting methodology builds on historical performance, industry trends, and the competitive moat that protects the business.

To start, examine historical owner earnings to establish a baseline. This historical data offers insight into how stable and predictable the cash flows have been over time. However, past performance is only one piece of the puzzle. You must also account for the sustainable growth rate of the business. This involves analyzing industry trends, market dynamics, and how the company’s competitive advantages—such as brand strength, cost efficiencies, or customer loyalty—position it for continued success. As highlighted in Buffett’s 1996 Annual Letter, understanding the long-term trends and staying focused on the underlying business quality is essential.

In projecting future cash flows, quantitative analysis plays a major role. You begin by applying a conservative growth rate to current owner earnings. This rate should reflect not only historical growth but also any changes in the business environment. For instance, if the industry is maturing or competitive pressures are increasing, it might be wise to lower your growth expectations.

Qualitative factors are equally important. Evaluate the management team’s track record and vision for the future. High-quality management can often navigate market headwinds more effectively, while strong corporate governance helps safeguard the company’s long-term interests. Additionally, consider broader market dynamics such as economic cycles, regulatory changes, and technological shifts.

Emphasizing conservative assumptions throughout this process is crucial. Overly optimistic forecasts can lead to inflated intrinsic value estimates, exposing investors to greater risk. By erring on the side of caution, you build a margin of safety into your projections, ensuring that the valuation remains robust even under less favorable conditions.

In summary, projecting future cash flows is a disciplined blend of quantitative forecasting and qualitative assessment. It is this rigorous, balanced approach that allows investors to estimate a business’s true earning potential and, ultimately, its intrinsic value.

4. Discounting Future Cash Flows to Present Value

The discounted cash flow (DCF) model is the cornerstone of modern valuation techniques, converting future cash flows into their present-day equivalents. At its heart, the DCF approach acknowledges the time value of money: a dollar earned in the future is inherently worth less than a dollar today. This principle allows investors to assess how much future earnings are worth in today’s dollars, forming the basis of an investment’s intrinsic value.

A critical component of the DCF model is determining the appropriate discount rate. According to Buffett’s 2007 Annual Letter, the discount rate should not merely mirror the risk-free rate—as represented by government securities—but must also include a risk premium that reflects the specific uncertainties of the business under evaluation. The formula often used to determine the discount rate is:

Discount Rate = Risk-Free Rate + Risk Premium

Here, the risk premium compensates investors for the additional risks they assume, ranging from industry volatility to competitive pressures and management effectiveness. This step is pivotal; even minor adjustments to the discount rate can dramatically alter the calculated intrinsic value.

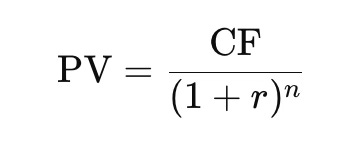

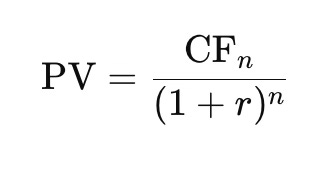

The process of discounting involves applying this rate to each forecasted cash flow. For every future period, the present value (PV) of a cash flow (CF) is calculated as:

where r is the discount rate and n represents the number of years into the future. By discounting each projected cash flow back to the present, and then summing these values, you arrive at the total present value of all future earnings.

This systematic method ensures that every future dollar is adjusted for risk and time, delivering a disciplined and transparent valuation framework. The careful selection of the discount rate and the meticulous application of the DCF model embody Buffett’s rigorous approach to investing—grounding high-level strategic decisions in a solid foundation of financial analysis.

5. Adjusting for Balance Sheet Strength: Current Assets and Debt

When we talk about a company’s value, it's not just about how much money it might make in the future. We also need to look at how strong its financial position is right now. This means checking out what the company owns (its current assets) and what it owes (its debt). Think of it like looking at a person’s bank account and credit card bills before deciding if they’re financially healthy.

Current Assets

Current assets are things a company owns that can be turned into cash quickly. This includes cash itself, money that customers owe (receivables), and items like inventory (products waiting to be sold). If a company has more cash than it needs for its everyday operations, we say it has "excess cash." When valuing a company, we add back any extra cash or assets that aren’t needed for its main business. This gives a better picture of the money available to its owners.

Debt Considerations

On the other side, we have debt. A company often borrows money to help grow its business or keep it running. The important number here is called "net debt." Net debt is simply the company’s total debt minus its cash and cash equivalents. The idea is, if a company has a lot of cash, it can use that money to pay off some of its debt. In other words, net debt shows how much the company truly owes after considering its available cash.

A simple way to see how this works is with the formula:

Equity Value = Enterprise Value − Net Debt

Here, Enterprise Value is the overall value of the company, and by subtracting net debt, we find out what the company is really worth to its shareholders.

Warren Buffett has always stressed the importance of a strong balance sheet. In his 1984 Annual Letter, he reminded us that a company with a healthy mix of assets and low net debt is better prepared for tough times. In simple terms, a robust balance sheet means the company can handle unexpected challenges and continue operating smoothly.

Overall, by looking at both current assets and debt, we get a fuller picture of a company’s financial strength—helping us decide if it’s a safe and smart investment.

6. Concrete Example: See’s Candies

Let’s illustrate these valuation principles with See’s Candies, a classic Buffett investment that perfectly demonstrates the power of a holistic valuation approach. Buffett often praised See’s Candies in his Annual Letters from the late 1970s and early 1980s, noting its strong cash flow, durable brand, and robust balance sheet.

Owner Earnings:

Imagine See’s Candies reported a net income of $10 million in a given year. In addition, it recorded $2 million in non-cash charges—such as depreciation and amortization—and incurred $1 million in maintenance capital expenditures (CAPEX), which are the funds needed to keep its existing assets operating efficiently. The calculation for owner earnings is:

Owner Earnings=$10 million+$2 million−$1 million=$11 million

This $11 million figure represents the true cash available from operations after making the necessary investments to maintain the business.

Future Cash Flow Projections:

Given the strength of See’s Candies’ brand and its pricing power, we project that its owner earnings will grow at a conservative annual rate of 5% over the next 10 years. This means:

Year 1: $11 million

Year 2: $11 million ×1.05≈$11.55 million

Year 3: $11.55 million ×1.05≈$12.13 million

… and so forth, with each year’s earnings growing by 5%.

These forecasts provide us with a set of future cash flows that reflect the company’s anticipated stable performance.

Discounting Process:

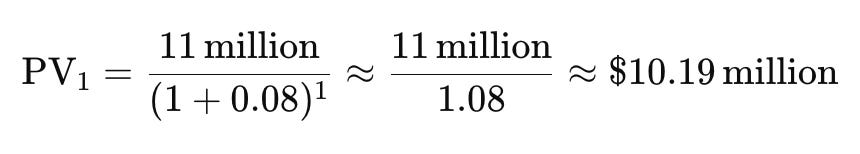

To convert these future cash flows into today’s dollars, we use the discounted cash flow (DCF) method. This approach acknowledges that money received in the future is worth less than money received today due to the time value of money. For this calculation, we apply a discount rate of 8% (which reflects a risk-free rate plus a modest risk premium).

The present value (PV) of each future cash flow is calculated with the formula:

where:

CFn is the cash flow in year n,

r is the discount rate (0.08), and

n is the number of years in the future.

For example, the present value of the Year 1 cash flow of $11 million would be:

You would repeat this calculation for each year (Years 2 through 10) and then sum all the discounted cash flows. Additionally, to account for cash flows beyond the 10-year period, a terminal value can be calculated and discounted back to the present using a similar method. In our illustrative example, the total present value of these cash flows might sum to approximately $100 million. This figure represents the estimated intrinsic value of the business based on the forecasted future earnings adjusted for risk and time.

Note: The numbers provided here are illustrative. Actual valuations would depend on the specific financial details and assumptions for the business.

Balance Sheet Adjustments:

Next, consider the company’s balance sheet. Suppose See’s Candies holds $5 million in excess cash and carries minimal debt, resulting in a net debt close to $0. Adding the excess cash to the enterprise value, we derive an equity value of:

Equity Value = $100 million + $5 million = $105 million

Margin of Safety:

Finally, if Berkshire Hathaway acquired See’s Candies for $80 million, the intrinsic value calculation reveals a substantial margin of safety—a cushion of $25 million or roughly 24% below the intrinsic value. This significant discount provides protection against unforeseen risks.

This concrete example demonstrates how combining owner earnings analysis, future cash flow projections, discounting, and balance sheet adjustments can yield a comprehensive valuation. As Buffett’s writings (see, for example, his late 1970s Annual Letters) show, this rigorous approach not only validates a sound investment decision but also offers a built-in margin of safety essential for long-term success.

7. Conclusion

In wrapping up our exploration of intrinsic value the Buffett way, it’s important to revisit the complete process that we’ve outlined. We started by determining the true cash-generating power of a business through owner earnings. By adjusting net income for non-cash expenses and subtracting maintenance capital expenditures, we obtained a clear picture of the cash available to the company. From there, we projected these owner earnings into the future, relying on historical performance, sustainable growth estimates, and an understanding of the company’s competitive moat.

Next, we applied the discounted cash flow (DCF) method to convert these future cash flows into today’s dollars. This step required us to choose a discount rate that reflects both the risk-free rate and a reasonable risk premium, ensuring that our valuation accounts for the time value of money and business-specific uncertainties. We then integrated balance sheet considerations, such as current assets and debt, by adding excess cash and subtracting net debt from the enterprise value to arrive at a more precise equity value. Finally, by applying a margin of safety, we ensured that our valuation not only captured the true worth of the company but also provided a buffer against unforeseen risks.

Warren Buffett’s timeless wisdom teaches us that true intrinsic value emerges from a careful blend of rigorous quantitative analysis and thoughtful qualitative judgment. His approach, as detailed in his Annual Letters (e.g., Buffett, 1986, Buffett, 2007), emphasizes the importance of relying on verified, real data to inform investment decisions.

I encourage you to delve deeper into Buffett’s Annual Letters for further insights into his methodology and to apply these principles in your own investment strategies. By doing so, you can build a resilient, value-driven portfolio grounded in sound, time-tested investment practices.

thanks, very nice article for non experts like me.

Would it be fair to say that net profit is more of an accounting construct, while owner earnings give a clearer picture of the actual cash available to a business owner?